The Koya Kingdom of Sierra Leone

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!

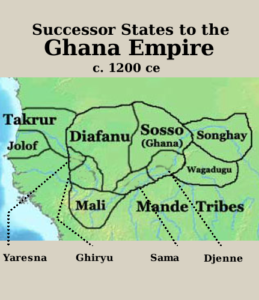

The history of the medieval Western Sudan is a tapestry of empires that shaped the region’s political, cultural, and economic

trajectories. While much has been written about the Ghana, Mali, and Songhay

empires, the Susu kingdom remains a lesser-known but equally crucial chapterin this narrative. This article explores the Susu kingdom’s historical relevance, geographical reach, and enduring connections to the Mano River and Sierra Leone, drawing on oral traditions, medieval chronicles, and Portuguese records. Stephan Bühnen’s (1994) insightful work provides the foundation for

this exploration.

The Rise

and Influence of the Susu Kingdom

The Susu kingdom rose to prominence after the decline of Ghana and before the rise of Mali, dominating the Futa Jalon and

Sankaran regions. This kingdom leveraged its strategic location and economic

resources, particularly its access to gold from the Bure mines, to become a

significant regional power (Bühnen, 1994). Its influence extended to the Upper

Niger and beyond, reaching regions close to the Mano River basin. Unlike Ghana

and Mali, Susu’s prominence south of Arab trade routes has contributed to its relatively

limited documentation in medieval Arabic sources.

The Susu people established political and

economic structures that laid the foundation for their later connections to

Sierra Leone and the Mano River region. The kingdom’s decline began with the

rise of Mali under Sunjata Keita and culminated in the 18th century with the

Fula jihad, but the Susu people’s legacy endured in their migration and

cultural influence across the region.

The Susu

and the Mano River Region

The Susu’s geographical and historical ties to the Mano River region are deeply rooted in their migrations, trade networks,

and cultural exchanges. Following the decline of their kingdom, the Susu moved

southward, settling in areas near the modern-day borders of Guinea, Liberia,

and Sierra Leone. These migrations brought them into contact with ethnic groups such as the Mende, Temne, and Kissi, thereby influencing the region’s demographics and cultural practices.

The Mano River served as a vital waterway for trade, linking inland goldfields with coastal trade centres. The Susu, known

for their expertise in trade and mining, played a pivotal role in facilitating the exchange of goods such as gold, kola nuts, and salt. Portuguese records

from the 15th and 16th centuries document the Susu’s active participation in

these networks, particularly along the coasts of Guinea and Sierra Leone

(Bühnen, 1994).

Cultural

and Religious Influence in Sierra Leone

The Susu’s migration into Sierra Leone had a lasting impact on the region’s cultural and religious landscape. Their early

adoption of Islam contributed to the spread of Islamic practices in the Mano

River basin and Sierra Leone. The Susu’s integration into local communities

also influenced linguistic and cultural exchanges. For example, the Susu

language, part of the Mande family, shares similarities with languages spoken

in Sierra Leone, reflecting their historical interactions and intermarriages.

In addition to their linguistic and religious

contributions, the Susu introduced governance practices that shaped local

chieftaincies. Oral traditions in Sierra Leone often highlight the Susu’s role in establishing political structures, emphasising their historical significance

in the region.

Portuguese

Accounts and European Records

European explorers and traders, particularly the Portuguese, encountered the Susu during their coastal expeditions. These records provide valuable insights into the Susu’s role as intermediaries in

regional trade. The Portuguese described the Susu as key players in gold exports, thereby linking the inland economies of the Western Sudan to the burgeoning Atlantic global trade networks (Bühnen, 1994). These accounts also highlight the Susu’s presence in Sierra Leone and their connections to the Mano River basin.

Sankaran

and the Susu Legacy

The Sankaran region, identified as the

heartland of the Susu kingdom, remained a significant power centre even after

the kingdom’s decline. The Konte lineage, central to Sankaran’s governance,

continued to exert influence, preserving the memory of Susu’s imperial past.

Bühnen (1994) notes that Sankaran’s traditions, including those preserved in

the Sunjata epic, reflect the cultural and political importance of the region.

The Susu’s transition into polities like Jalo

and their eventual absorption into the Muslim Fula state of Futa Jalon

illustrate a pattern of continuity and adaptation. Despite losing political

independence, the Susu maintained their identity, leaving a lasting imprint on

the cultural and political fabric of the Mano River region and Sierra Leone.

Conclusion

The Susu kingdom represents a critical yet

understudied chapter in West African history. Its influence extended from the

Futa Jalon and Sankaran regions to the Mano River and Sierra Leone, shaping

trade, culture, and religion. By examining oral traditions, chronicles, and

European records, scholars like Stephan Bühnen (1994) have illuminated the

Susu’s enduring legacy. Today, their contributions remain a testament to the

dynamic interplay of migration, trade, and cultural exchange in precolonial

Africa.

References

Bühnen, S. (1994). In quest of Susu. History

in Africa, 21, 1–47.https://www.jstor.org/stable/3171880