4. Fadenya vs. Badenya: Rivalry and Cohesion in Politics

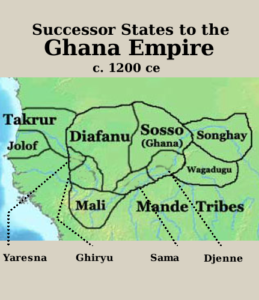

Within Mandé political thought, the concepts of Fadenya and Badenya represent two fundamental forces that shape the dynamics of leadership and social organisation. Fadenya, translated as “father-childness,” embodies competition, ambition, and the drive for innovation. It is the motivating force that encourages individuals and groups to challenge existing hierarchies, pursue reform, and instigate change within society. This spirit of rivalry and contestation is essential for progress and adaptation, as it pushes communities to confront corruption, reimagine institutions, and embrace new possibilities.

In contrast, Badenya, or “mother-childness,” signifies cohesion, respect for tradition, and the pursuit of collective harmony. Badenya is the stabilising force that fosters unity, preserves social bonds, and upholds communal values. It ensures that, even as individuals strive for personal advancement or reform, there remains a foundation of trust and mutual respect that binds the group together.

These dual forces do not operate in isolation. Rather, they work in tandem to create a balanced political system. A society driven exclusively by Fadenya may experience rapid innovation and transformation, but risks becoming fragmented and unstable. Conversely, an overemphasis on Badenya can result in stagnation, nepotism, and resistance to necessary change.

This interplay can be vividly illustrated: Fadenya is the fire that forges transformation, igniting new possibilities and driving societal evolution. Badenya, meanwhile, is the clay that binds society together, ensuring that change does not come at the expense of cohesion and enduring community values.

Balancing Fadenya and Badenya in Reformist Leadership

A reformist leader who seeks to address corruption within established elites must skillfully embody both Fadenya and Badenya. By embracing Fadenya, the leader channels ambition and the drive for change, challenging entrenched interests and advocating for institutional reform. This spirit of rivalry and contestation is essential for breaking down barriers and initiating progress.

At the same time, the leader must appeal to Badenya to uphold social cohesion and maintain trust in institutions. By fostering unity and respect for tradition, the leader ensures that the pursuit of change does not destabilise the community or erode the bonds that hold society together. The effective integration of both Fadenya and Badenya allows for transformative leadership that balances innovation with stability, enabling reform to occur within a framework of enduring communal values.