Archive

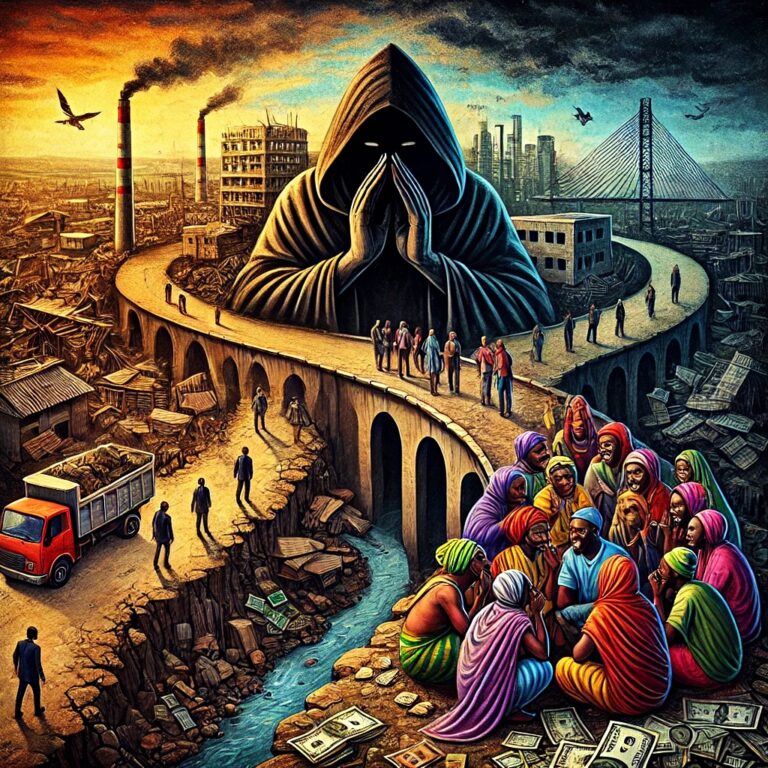

Understanding Poverty in West Africa

February 13, 2025Anthropology,Blog,Google Blogger,Political Economies

West Africa is endowed with vast natural resources and a rich cultural heritage, yet it remains one of the poorest...

The Role of Education in Advancing Development in Sierra Leone: A Focus on Cultural Integration, Mother Tongue Instruction, and Deductive Learning

January 1, 2025Cognative Psychology,Education,Mother Tongue

Education is more than a tool for personal growth; it is a catalyst for national transformation. In Sierra Leone, the...

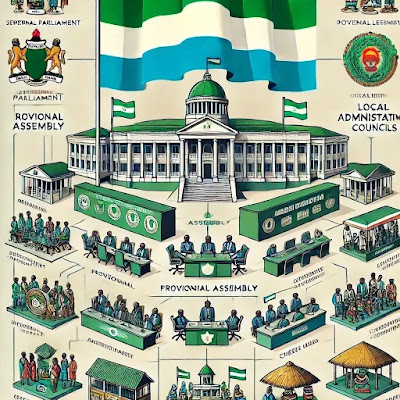

The Rationale for Chiefs as Arbitrators and Trustees of Resources in Sierra Leone

February 24, 2025Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

A Historical, Cultural, Political, and Economic Analysis The role of chiefs as arbitrators and trustees of resources...

The Potential Impact of Emerging Global Political Realities on Resource-Rich but Underdeveloped Countries

March 2, 2025Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

By Mohamed Boye Jallo Jamboria 1. Abstract This paper explores the implications of the emerging multipolar global order on resource-rich...

The Politics of Polarization in Sierra Leone: Navigating Division in a Culturally Homogeneous Society

February 17, 2025Anthropology,Blog,Google Blogger,History,Political Economies,Upper Guinea,West Africa

Sierra Leone is a nation that embodies a paradox of cultural unity and political fragmentation. Despite being...

The Historical and Recent Trauma Experienced by Sierra Leoneans: Behavioural Patterns Rooted in Survival Instincts

January 2, 2025Beliefs,Epigenetics,Social Psychology,Sociology

Sierra Leone, a nation rich in culture and natural resources, has endured centuries of trauma that shape its social fabric...

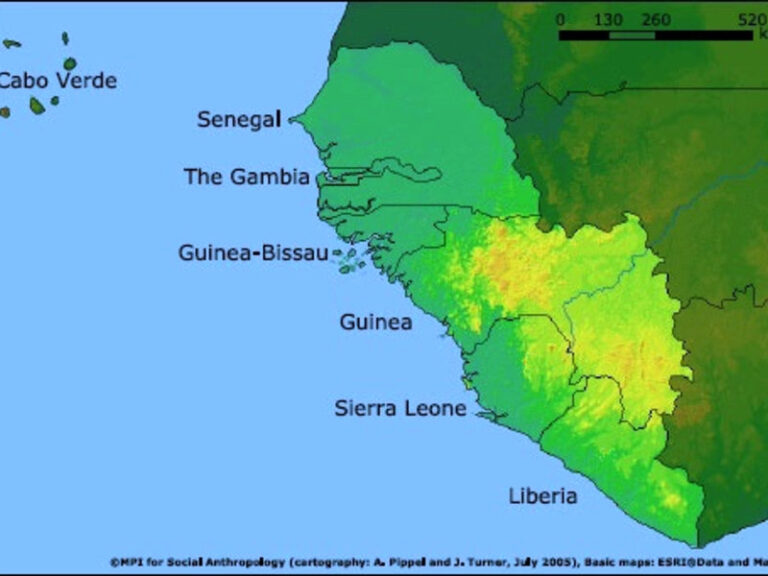

The Anthropology of the Upper Guinea Coast (10th Century to Present)

January 19, 2025Anthropology,Upper Guinea,West Africa

Introduction The Upper Guinea Coast, encompassing modern-day Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and parts of Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire, has long...

The Class and Respect Issues Among the Africans

January 9, 2025Anthropology,Caste system,Upper Guinea,West Africa

Class and respect dynamics within African societies and the African diaspora represent an intricate interplay of history, culture, and socio-economic...

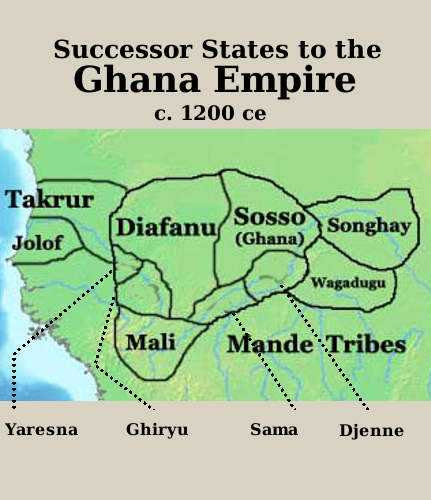

Show me your History;I’ll show you your greatness!

May 11, 2019Post

The Malinke connection of Sierra Leone The country called Sierra Leone today has a history with a very strong Malinke...

Top News

March 12, 2025

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

Popular News

This Article explores the layered consequences of modernization in African post-colonial contexts, focusing on how political gaslighting...

March 12, 2025

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

Recent Topic

This Article explores the layered consequences of modernization in African post-colonial contexts, focusing on how...

Weekly News

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

ScanAfrik Forbundet

Bygbakanda00

March 12, 2025

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

Impunity on the Rise

Bygbakanda00

March 5, 2025

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

African Culture

Bygbakanda00

March 5, 2025

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

The Potential Impact of Emerging Global Political Realities on Resource-Rich but Underdeveloped Countries

Bygbakanda00

March 2, 2025

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

Google Blogger

Bygbakanda00

February 27, 2025

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

Archive

Bygbakanda00

February 26, 2025

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

The Rationale for Chiefs as Arbitrators and Trustees of Resources in Sierra Leone

Bygbakanda00

February 24, 2025

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

RbnLiveTV

Bygbakanda00

February 20, 2025

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa

Top News

March 12, 2025

Advocacy,African Culture,Anthropology,Attitudinal Change,Beliefs,Blog,Books,Caste system,Cognative Psychology,Culture,economics,Education,Epigenetics,Esoterics,globaltrends,Google Blogger,History,Metaphysics,Mother Tongue,News,Perceptions,Political Economies,Post,Social Justice,Social Psychology,Sociology,Upper Guinea,vlog,West Africa