The Politics of Polarization in Sierra Leone: Navigating Division in a Culturally Homogeneous Society

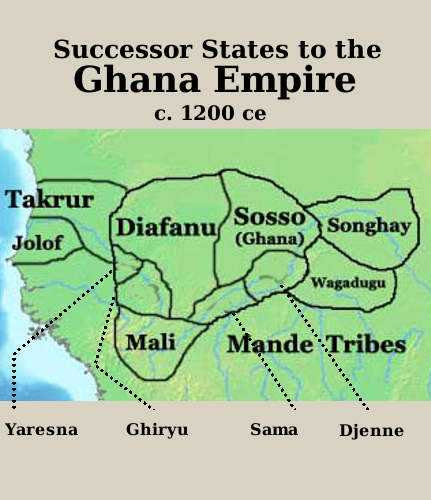

Sierra Leone is a nation that embodies a paradox of cultural unity and political fragmentation. Despite being one of the most culturally and religiously homogeneous countries in Africa, the country remains deeply polarized along regional and partisan lines. The dominant Islamic faith and the Fulani-Mande cultural foundation create profound commonalities among Sierra Leone’s major ethnic groups, including the Mende, Temne, Limba, and Mandingo. Inter-ethnic marriages, the widespread use of common surnames, and the overlapping linguistic traditions suggest that the country should, in theory, have a strong sense of national unity. However, political fragmentation has persisted as a significant challenge, sustained by historical legacies, elite manipulation, and institutional weaknesses. Unlike many African nations where ethnic and religious divisions are the main sources of conflict, Sierra Leone demonstrates how political identity can override cultural commonalities, fuelling instability. Political polarization in Sierra Leone has been reinforced through decades of historical, colonial, and post-colonial political manoeuvring. The two dominant parties, the All People’s Congress (APC) and the Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP), have historically entrenched regional loyalties and reinforced a winner-takes-all system of governance. This political culture has created an environment where electoral victories often lead to the systematic exclusion of the opposition, heightening political tensions and fostering long-term instability. To understand why these divisions, persist despite a shared cultural foundation, it is essential to examine Sierra Leone’s historical trajectory, the role of secret societies, the importance of inter-ethnic surnames, and the ways political elites have strategically manipulated these identities to maintain power. The political divisions in Sierra Leone have deep roots in the colonial governance structures established by the British. The colonial rulers implemented a dual system of governance, in which the north was governed through indirect rule—granting significant administrative power to local chiefs—while the south and east were subjected to direct rule under colonial officers. This system created significant economic and infrastructural disparities between the two regions, fuelling political competition and long-term rivalries (Bangura, 2015). At independence in 1961, these colonial divisions continued to shape Sierra Leone’s political landscape. The SLPP, which had led the independence movement, was largely associated with the Mende-dominated south and east, while the APC, founded in the 1960s, built its political base in the predominantly Temne and Limba northern regions. Over the decades, political power has oscillated between these two dominant parties, each reinforcing regional loyalties and prioritizing its strongholds over national governance. The civil war (1991–2002) further aggravated these divisions. While the war was driven by grievances related to corruption, economic marginalization, and centralized governance, it was also heavily influenced by regional factionalism. The Revolutionary United Front (RUF) insurgency, initially framed as a rebellion against state corruption, became deeply entangled in regional power struggles. Though the war ended in 2002, the mistrust it cultivated between political actors has continued to shape electoral politics and governance, making it difficult for the country to move beyond regional partisanship. Despite the deep political divisions, Sierra Leone remains remarkably homogeneous in cultural and linguistic identity. One of the strongest indicators of this shared heritage is the prevalence of common surnames across ethnic groups. Names such as Koroma, Kamara, Conteh, Bangura, Fofanah, and Sesay are widely used among the Temne, Limba, Mandingo, and Mende peoples. These surnames have deep historical origins, tracing back to Fulani, Senegambian, Konyaka, Malinke, and Gbandi-Loko migrations that shaped Sierra Leone’s demographics. The Koroma surname is particularly significant. While commonly associated with the Limba and Temne, it is also found among the Mende-speaking population. This widespread presence reflects the extensive influence of Mande heritage across Sierra Leone. Historically, the Koroma name has been linked to warriors, traders, and political leaders who played crucial roles in both pre-colonial and colonial Sierra Leone. Its presence across ethnic groups also suggests historical ties to the Mali and Songhai Empires, which facilitated the spread of Mande culture, language, and surnames across West Africa. Similarly, the Fofanah surname, widely associated with the Mandingo, Temne, and Mende, has strong Senegambian roots. Many Fofanah families trace their lineage to Fulani-Mande Islamic scholars and traders who migrated southward from Mali and Guinea into Sierra Leone. Their integration into different communities over centuries led to the widespread adoption of the Fofanah name across various ethnic groups. Many individuals bearing the Fofanah name have historically played key roles in Islamic scholarship, governance, and commerce. The Sesay surname is another example of a Mande-Senegambian name that has been adopted across multiple ethnic groups in Sierra Leone. Like the Fofanah name, Sesay is historically linked to Malian and Senegambian expansions, particularly during the height of the Mali Empire’s trade networks. Families with the Sesay name were influential in establishing trade routes, religious schools, and political networks, facilitating economic and social integration across different regions. The name’s widespread presence across various districts reinforces the idea that Sierra Leone’s ethnic groups have long been connected through trade, migration, and intermarriage. Beyond surnames, place names in Sierra Leone also reflect Mande, Fulani, and Senegambian influences. The Koya region, which exists in both Port Loko and Kenema districts, directly references the Mane warriors who established strongholds in Sierra Leone and the broader Mano River Union region. The recurring names Gbendembu (in Bombali) and Nongowa (in Kenema) highlight the influence of Gbandi, Loko, and Mande-speaking groups in shaping Sierra Leone’s geographic and cultural landscape. The place name Sumbuya, found in almost every district, further underscores the deep historical interactions that have shaped Sierra Leone’s modern identity. One of the most enduring cultural institutions that binds Sierra Leone together is the predominance of Mande secret societies, particularly the Poro and Sande societies. These secret societies, which originated from the broader Mande cultural sphere, have played a critical role in shaping political, spiritual, and social life in Sierra Leone. The Poro society, which is primarily for men, functions as an institution of governance, education, and moral regulation. It serves as a training ground

Understanding Poverty in West Africa

West Africa is endowed with vast natural resources and a rich cultural heritage, yet it remains one of the poorest regions in the world. According to the World Bank (2020), poverty rates in West Africa exceed 40%, with some countries, such as Niger and Mali, experiencing extreme deprivation. The persistence of poverty in the region is not merely a result of economic challenges but is deeply embedded in historical, social, and political structures that perpetuate inequality. Among the key factors sustaining poverty are the caste system, weak governance, economic mismanagement, impunity, and historical trauma. This article explores these interrelated issues and examines how decentralisation and the inclusion of traditional governance structures can contribute to poverty alleviation. Poverty in West Africa is deeply rooted in historical, political, and social structures that sustain inequality. The caste system, corruption, economic exclusion, impunity, and historical trauma all contribute to the persistence of poverty. Addressing these challenges requires a comprehensive strategy that includes decentralization, the integration of traditional governance structures, judicial and political reforms, and investment in education and economic empowerment. By embracing localised and inclusive governance models, West African societies can break the cycle of poverty and create a more equitable future. Although the caste system is most commonly associated with South Asia, it is also a defining social structure in many West African societies. Countries such as Mali, Senegal, Guinea, and Niger have long-standing caste hierarchies that dictate an individual’s social status, profession, and economic opportunities (Tamari, 1991). The caste system in these societies divides people into hierarchical groups, often limiting access to education, employment, and land ownership for marginalized castes. For example, in Mali and Senegal, the griots (oral historians) and Nyamakalaw (artisan castes) are often denied access to political power and high-status professions, while noble and warrior castes control economic and political resources (Bellagamba et al., 2013). Additionally, descendants of slaves in countries such as Mauritania and Niger continue to experience systemic discrimination and economic exclusion. The rigid social stratification creates a cycle of poverty, where marginalized groups struggle to access opportunities for social mobility. The Haratine Community in Mauritania for example is a historically enslaved group in Mauritania, continues to face systemic discrimination. Although slavery was officially abolished in 1981, many Haratine remain in servitude-like conditions, working as unpaid domestic labourers (Minority Rights Group, 2021). Limited access to education and land ownership perpetuates their economic marginalization, leaving them trapped in intergenerational poverty. Governance in many West African countries is characterised by centralised power structures, weak institutions, and widespread corruption. Political elites often control state resources, diverting them for personal gain rather than for public investment in infrastructure, healthcare, and education (Transparency International, 2021). As a result, many essential public services remain underfunded, leaving large portions of the population without access to basic amenities. A Vicious Cycle Corruption has a direct impact on poverty by limiting economic opportunities and undermining development efforts. In Nigeria, for example, the mismanagement of oil revenues has led to severe underdevelopment in the Niger Delta region. Despite being rich in oil, the region suffers from high unemployment rates, poor infrastructure, and environmental degradation due to unchecked exploitation by multinational corporations and corrupt government officials (Okonkwo, 2019). Many West African economies remain dependent on extractive industries such as mining, oil, and agriculture. However, these industries are often controlled by multinational corporations in partnership with political elites, leaving little economic benefit for the general population (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012). Additionally, rural communities, particularly subsistence farmers, struggle with insecure land tenure, making it difficult for them to invest in agricultural production or access credit (World Bank, 2020). In Sierra Leone, large-scale land acquisitions by foreign agribusiness companies have displaced thousands of farmers, depriving them of their livelihoods. Many of these deals are brokered by corrupt government officials who prioritize foreign investment over the well-being of local populations (Moyo & Yeros, 2011). As a result, communities that rely on agriculture are left impoverished, with limited means of survival. Further,the history of slavery, colonialism, and post-independence dictatorship has left deep psychological and social scars in West African societies. Centuries of exploitation have fostered a culture of fear and resignation, where individuals often feel powerless to challenge corrupt leadership or demand accountability. Political Repression and Fear In many West African countries, political dissent is met with repression. Governments use intimidation tactics, including arrests, media censorship, and even violence, to silence critics (Gyimah-Boadi, 2015). This culture of fear discourages active political participation, allowing corrupt regimes to maintain power unchallenged. The effects of armed conflicts in West Africa—such as civil wars in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Côte d’Ivoire—have had long-term economic and psychological consequences. Many individuals who experienced violence during these conflicts continue to suffer from trauma, reducing their ability to engage in economic activities or civic participation (Richards, 1996). Additionally, the destruction of infrastructure during conflicts has left many communities without access to essential services, further deepening poverty. The lack of accountability for political and economic misconduct perpetuates poverty by allowing corruption and exploitation to thrive. When powerful individuals are not held accountable for crimes such as embezzlement, electoral fraud, or human rights violations, economic mismanagement continues unchecked (Ndikumana & Boyce, 2011). In Guinea, successive governments have engaged in corrupt practices, including illicit mining deals and public fund embezzlement. Despite numerous reports of corruption, few officials have been prosecuted, creating an environment where public resources are continuously siphoned away from development projects (Hoffmann & Patel, 2017). Bringing Governance Closer to the People Decentralization is a governance strategy that involves transferring decision-making power, resources, and responsibilities from central governments to local authorities. This approach aims to bring governance closer to the people, allowing communities to have greater control over their own development. Decentralization has gained traction as an effective means of improving governance in many parts of the world, particularly in West Africa, where centralized state structures have often struggled to meet the needs of diverse and widely dispersed populations (Smoke, 2003). Research suggests that decentralized governance leads to better resource allocation, increased accountability, and

Reconstructing a Forgotten Empire and its Connection to the Mano River and Sierra Leone

The history of the medieval Western Sudan is a tapestry of empires that shaped the region’s political, cultural, and economic trajectories. While much has been written about the Ghana, Mali, and Songhay empires, the Susu kingdom remains a lesser known but equally important chapter in this narrative. This article explores the Susu kingdom’s historical relevance, geographical reach, and enduring connections to the Mano River and Sierra Leone, drawing on oral traditions, medieval chronicles, and Portuguese records. Stephan Bühnen’s (1994) insightful work provides the foundation for this exploration. The Rise and Influence of the Susu Kingdom The Susu kingdom rose to prominence after the decline of Ghana and before the rise of Mali, dominating the Futa Jalon and Sankaran regions. This kingdom leveraged its strategic location and economic resources, particularly its access to gold from the Bure mines, to become a significant regional power (Bühnen, 1994). Its influence extended to the Upper Niger and beyond, reaching regions close to the Mano River basin. Unlike Ghana and Mali, Susu’s prominence south of Arab trade routes has contributed to its relatively limited documentation in medieval Arabic sources. The Susu people established political and economic structures that laid the foundation for their later connections to Sierra Leone and the Mano River region. The kingdom’s decline began with the rise of Mali under Sunjata Keita and culminated in the 18th century with the Fula jihad, but the Susu people’s legacy endured in their migration and cultural influence across the region. The Susu and the Mano River Region The Susu’s geographical and historical ties to the Mano River region are deeply rooted in their migrations, trade networks, and cultural exchanges. Following the decline of their kingdom, the Susu moved southward, settling in areas near the modern-day borders of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. These migrations brought them into contact with ethnic groups such as the Mende, Temne, and Kissi, influencing the demographics and cultural practices of the region. The Mano River served as a vital waterway for trade, linking inland goldfields with coastal trade centers. The Susu, known for their expertise in trade and mining, played a pivotal role in facilitating the exchange of goods such as gold, kola nuts, and salt. Portuguese records from the 15th and 16th centuries document the Susu’s active participation in these networks, particularly along the coasts of Guinea and Sierra Leone (Bühnen, 1994). Cultural and Religious Influence in Sierra Leone The Susu’s migration into Sierra Leone had a lasting impact on the region’s cultural and religious landscape. Their early adoption of Islam contributed to the spread of Islamic practices in the Mano River basin and Sierra Leone. The Susu’s integration into local communities also influenced linguistic and cultural exchanges. For example, the Susu language, part of the Mande family, shares similarities with languages spoken in Sierra Leone, reflecting their historical interactions and intermarriages. In addition to their linguistic and religious contributions, the Susu introduced governance practices that shaped local chieftaincies. Oral traditions in Sierra Leone often highlight the Susu’s role in establishing political structures, emphasizing their historical significance in the region. Portuguese Accounts and European Records European explorers and traders, particularly the Portuguese, encountered the Susu during their coastal expeditions. These records provide valuable insights into the Susu’s role as intermediaries in regional trade. The Portuguese described the Susu as key players in gold exports, which linked the inland economies of the Western Sudan to the burgeoning global trade networks of the Atlantic (Bühnen, 1994). These accounts also highlight the Susu’s presence in Sierra Leone and their connections to the Mano River basin. Sankaran and the Susu Legacy The Sankaran region, identified as the heartland of the Susu kingdom, remained a significant power centre even after the kingdom’s decline. The Konte lineage, central to Sankaran’s governance, continued to exert influence, preserving the memory of Susu’s imperial past. Bühnen (1994) notes that Sankaran’s traditions, including those preserved in the Sunjata epic, reflect the cultural and political importance of the region. The Susu’s transition into polities like Jalo and their eventual absorption into the Muslim Fula state of Futa Jalon illustrate a pattern of continuity and adaptation. Despite losing political independence, the Susu maintained their identity, leaving a lasting imprint on the cultural and political fabric of the Mano River region and Sierra Leone. Conclusion The Susu kingdom represents a critical yet understudied chapter in West African history. Its influence extended from the Futa Jalon and Sankaran regions to the Mano River and Sierra Leone, shaping trade, culture, and religion. By examining oral traditions, chronicles, and European records, scholars like Stephan Bühnen (1994) have illuminated the Susu’s enduring legacy. Today, their contributions remain a testament to the dynamic interplay of migration, trade, and cultural exchange in precolonial Africa. References Bühnen, S. (1994). In quest of Susu. History in Africa, 21, 1–47.https://www.jstor.org/stable/3171880