By Mohamed Boye Jallo Jamboria1. Abstract This paper explores the implications of the emerging multipolar global order on resource-rich but underdeveloped countries, using Sierra Leone as a case study. The analysis highlights how the decline of U.S. dominance and the rise of China and other regional powers create new challenges and opportunities. Key risks include economic dependency, neo-colonial exploitation, and environmental degradation. This paper emphasizes the need for donor-dependent nations like Sierra Leone to revisit their economic planning policies to focus on governance, economic diversification, and sustainable resource management. The study recommends a proactive approach centered on institutional strengthening, fair trade, and transparent governance to transform resource wealth into sustainable development. 2. Introduction The global political landscape is undergoing significant transformation, characterized by a shift from U.S.-led unipolarity to a multipolar world with rising powers such as China, India, and Russia (Adams, 2021). For resource-rich but underdeveloped countries like Sierra Leone, this shift presents both unprecedented risks and opportunities. Sierra Leone, with its abundant mineral resources—diamonds, iron ore, rutile, and bauxite—offers a compelling case study of the "resource curse" phenomenon, where countries rich in natural resources often experience poor governance, low economic diversification, and high dependency on external aid (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012). Despite substantial natural wealth, Sierra Leone remains one of the poorest countries globally, with over 50% of its population living below the poverty line (World Bank, 2020). This paper argues that the changing global order necessitates a fundamental rethinking of economic planning policies in donor-dependent nations. Effective governance, economic diversification, and transparent management of resource wealth are essential to break the cycle of dependency and ensure sustainable development. 3. Historical Context: Post-WWII Decolonization and Economic Realities Post-World War II decolonization was significantly influenced by the economic and strategic interests of Western powers. European nations, economically devastated by the war, prioritized rebuilding their economies over maintaining costly colonial administrations. The U.S.-sponsored Marshall Plan provided financial support to Western Europe but also pressured European powers to dismantle their colonial empires to open markets for American goods (Jones, 2019). Sierra Leone gained independence in 1961 amid this shifting geopolitical context. However, the economic legacy of colonialism persisted, characterized by a focus on raw material exports and minimal investment in local industries. This dependence on extractive industries has continued to shape Sierra Leone's economic planning, limiting diversification and making the country vulnerable to global commodity price fluctuations (Brown, 2020). The experience of post-WWII decolonization underscores the need for Sierra Leone to revisit its economic planning policies, focusing on reducing dependency on primary commodities and fostering local value addition. 4. The Emerging Multipolar World Order 4.1 The Decline of U.S. Dominance The decline of U.S. dominance is evidenced by economic stagnation, rising national debt, and political polarization, which have constrained its ability to unilaterally shape global economic policies (Adams, 2021). For Sierra Leone, this decline has both positive and negative implications. On one hand, it opens opportunities to diversify trade and investment partners. On the other hand, it reduces the leverage Sierra Leone might have had in securing favourable trade terms under a U.S.-led liberal economic order. The retreat of the U.S. from multilateral institutions and its reduced aid budgets also mean that Sierra Leone must seek alternative sources of funding for infrastructure and development projects. This has led to a growing dependence on China and other emerging powers, whose aid and investments often come with fewer governance conditions but higher long-term risks (Lee, 2020). 4.2 Rise of China and Other Emerging Powers China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has become a cornerstone of its global strategy, focusing on infrastructure investments in developing countries, including Sierra Leone. Chinese investments in roads, ports, and energy projects in Sierra Leone have significantly improved the country’s infrastructure. However, many of these projects have been financed through loans secured by natural resources, raising concerns about debt sustainability and sovereignty risks (Brautigam, 2020). India and Turkey have also increased their presence in Sierra Leone, competing for access to resources and strategic markets. This growing multipolarity presents an opportunity for Sierra Leone to leverage competition among emerging powers to secure better investment terms. However, it also necessitates a sophisticated economic planning strategy to balance these competing interests effectively. 5. Challenges for Resource-Rich but Underdeveloped Countries: The Case of Sierra Leone 5.1 Economic Dependence on Extractive Industries Sierra Leone’s economy is heavily reliant on mineral exports, which accounted for over 80% of its export revenues in 2019 (World Bank, 2020). This dependence on primary commodities exposes the economy to significant risks due to volatile global commodity prices. The 2014-2016 collapse in iron ore prices, for example, led to a severe recession, highlighting the dangers of an undiversified economic base. To address this issue, Sierra Leone must revisit its economic planning policies to promote industrialization and value addition to raw materials. Investments in agribusiness, manufacturing, and services can help reduce reliance on mineral exports and create more resilient economic structures. 5.2 Institutional Weakness and Governance Challenges Corruption and weak institutions have been significant impediments to effective resource management in Sierra Leone. The country ranked 119th out of 180 on the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index in 2020, reflecting widespread governance challenges (Transparency International, 2020). Institutional reforms focusing on transparency, accountability, and the rule of law are essential for Sierra Leone to manage its resource wealth effectively. Strengthening anti-corruption agencies, enhancing judicial independence, and implementing transparent contract negotiation processes can help attract sustainable investments and improve public confidence in the government's ability to manage resource revenues. 5.3 Infrastructure Deficits and Technological Dependence Sierra Leone's infrastructure deficit is a significant barrier to economic diversification and inclusive growth. Poor road networks, unreliable electricity supply, and limited digital infrastructure hinder the development of manufacturing and services sectors (Smith, 2019). Chinese investments have addressed some of these gaps, but the lack of technology transfer and skills development raises concerns about the sustainability of these projects. Economic planning should prioritize investments in transport, energy, and digital infrastructure that support a diversified economic base rather than focusing solely on resource extraction. Developing local technical capacities through vocational training and partnerships with foreign investors can also help reduce technological dependence. 5.4 Environmental Degradation and Socioeconomic Costs Unregulated mining has led to severe environmental degradation in Sierra Leone, including deforestation, water pollution, and loss of biodiversity. These environmental costs disproportionately affect rural communities, exacerbating poverty and social tensions (Greenpeace, 2021). Economic planning must integrate environmental sustainability into resource management strategies. Strengthening environmental regulations, enforcing corporate social responsibility (CSR) standards, and investing in renewable energy sources can help mitigate the environmental impact of resource extraction. 6. Strategic Risks in the New Global Order 6.1 Debt Traps and Financial Dependencies China’s infrastructure investments in Sierra Leone have been primarily financed through concessional loans tied to natural resource exports. The IMF reported that Sierra Leone’s debt-to-GDP ratio reached over 70% in 2020, raising concerns about debt sustainability and the risk of default (IMF, 2020). The Lungi Bridge project, for instance, which was to be financed through a Chinese loan, sparked debates on its economic viability and the potential loss of sovereignty if Sierra Leone failed to service its debts. Debt dependencies not only constrain fiscal space for social and developmental spending but also limit policy autonomy. Revisiting loan agreements to include more favourable repayment terms and prioritizing grant financing over loans can help mitigate these risks. 6.2 Exploitative Trade Agreements and Resource Control Many of Sierra Leone's trade agreements prioritize raw material exports without sufficient provisions for local value addition or technology transfer. These agreements often include tax holidays and other incentives for foreign investors, reducing potential public revenues. For example, the agreements with iron ore mining companies in Tonkolili and Marampa provided significant tax breaks but limited local employment and technology transfer benefits (Stiglitz, 2017). Revisiting these trade agreements to incorporate local content requirements, fair revenue-sharing mechanisms, and mandatory technology transfer clauses is essential to maximize the benefits of resource wealth. Strengthening the capacity of trade negotiators and ensuring parliamentary oversight of trade agreements can also help address these challenges. 6.3 Neo-Colonialism through Technology and Finance The Digital Silk Road initiative by China has included investments in telecommunications infrastructure in Sierra Leone, such as fibre optic networks and surveillance systems. While these projects enhance digital connectivity, they also create new forms of dependency by locking Sierra Leone into Chinese technology standards and financial systems (Feng, 2019). To avoid a digital form of neo-colonialism, Sierra Leone should prioritize diversifying its technology partnerships and investing in local IT capabilities. Developing a national data sovereignty strategy that emphasizes cybersecurity, local data storage, and regulatory oversight can help mitigate the risks of external control over critical digital infrastructure. 7. Revisiting Economic Planning Policies in Donor-Dependent Nations: Lessons from Sierra Leone 7.1 Leveraging Resource Wealth for Sustainable Development Sierra Leone’s dependence on donor aid and concessional loans highlights the need for a sovereign wealth fund to manage resource revenues transparently. By investing resource wealth in infrastructure, education, and healthcare, a sovereign wealth fund can transform mineral wealth into long-term development outcomes (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012). Norway’s Oil Fund provides a successful model for Sierra Leone to emulate, with clear governance structures, transparency in resource revenue management, and a focus on intergenerational equity. Establishing a similar fund, coupled with fiscal rules that cap how much of the resource revenue can be spent annually, could help Sierra Leone manage resource volatility and invest in diversified development projects. 7.2 Institutional Strengthening and Good Governance Effective resource management requires strong institutions that can enforce contracts, regulate industries, and combat corruption. Sierra Leone’s Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) has made some progress in prosecuting high-profile cases, but the lack of judicial independence and political interference remains a significant challenge (Transparency International, 2020). Institutional reforms should focus on enhancing the independence of the judiciary, strengthening anti-corruption agencies, and ensuring transparency in public procurement. Implementing international standards such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) can also improve transparency in the management of resource revenues (EITI, 2018). 7.3 Economic Diversification and Human Capital Development Sierra Leone’s heavy reliance on extractive industries underscores the need for economic diversification. Expanding the agribusiness sector, which employs over 60% of the population, and promoting light manufacturing can create more resilient and inclusive growth. Government policies should focus on improving access to credit for small and medium enterprises (SMEs), investing in agricultural value chains, and reducing trade barriers within the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) region (Smith, 2019). Investing in human capital is equally crucial. Sierra Leone’s education sector faces significant challenges, including low enrolment rates and inadequate vocational training. Aligning education policies with the demands of a diversified economy—such as training in agribusiness, manufacturing, and information technology—can enhance productivity and reduce dependence on resource exports. 7.4 Fair Trade and Transparent Financial Practices Revisiting trade agreements to prioritize fair trade practices is essential for Sierra Leone’s economic resilience. This includes renegotiating existing agreements to incorporate provisions for local content, value addition, and equitable revenue sharing. Regional trade agreements, such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), offer opportunities for Sierra Leone to expand its markets and reduce dependency on traditional trade partners (Stiglitz, 2017). Transparency in financial practices is also critical. Adopting the EITI standards and requiring full disclosure of mining contracts can reduce corruption risks and ensure that resource revenues are used for public benefit. Strengthening the role of the Parliament in overseeing financial agreements and resource contracts can enhance accountability and prevent exploitative practices. Final Words The emerging multipolar world order presents both risks and opportunities for resource-rich but underdeveloped countries like Sierra Leone. While investments from China and other emerging powers offer prospects for infrastructure development, they also raise concerns about debt dependency, sovereignty risks, and neo-colonial economic relationships. To navigate these challenges effectively, Sierra Leone must revisit its economic planning policies with a focus on institutional strengthening, economic diversification, and transparent management of resource wealth. Establishing a sovereign wealth fund, enhancing governance frameworks, and prioritizing education and infrastructure investments can transform mineral wealth into a foundation for inclusive and sustainable development. By adopting a proactive and transparent approach to managing its resource wealth, Sierra Leone can reduce dependency on donor aid, build a resilient economy, and ensure that its resource wealth benefits all citizens. 9. References

-

-

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. Crown Publishing Group. -

Adams, M. (2021). The Decline of American Power: Strategies and Implications. Harvard University Press.

-

Brautigam, D. (2020). The Dragon's Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa. Oxford University Press.

-

EITI. (2018). Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative Standard. Retrieved from www.eiti.org

-

Feng, Y. (2019). China's Digital Silk Road: Strategic Implications for the Global Order. Tsinghua University Press.

-

IMF. (2020). Sierra Leone Debt Sustainability Analysis. International Monetary Fund.

-

Lee, C. (2020). The Belt and Road Initiative: Economic and Strategic Implications. Springer.

-

Smith, A. (2019). Infrastructure Development in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities. Oxford University Press.

-

Stiglitz, J. E. (2017). Globalization and Its Discontents Revisited: Anti-Globalization in the Era of Trump. W.W. Norton & Company.

-

Transparency International. (2020). Corruption Perceptions Index 2020. Retrieved from www.transparency.org

-

- World Bank. (2020). Sierra

Leone Economic Update: Promoting Inclusive Growth. World Bank

Publications.

About the Writer Mohamed Boye Jallo Jamboria is a Sierra Leonean educator, consultant, and writer based in Bergen, Norway, with a diverse professional background in rural community development, agribusiness, and public service. From 2011 to 2015, he served two terms as a councillor for the Liberal Party in Lindås Municipality, Norway, and was a member of the Gender and Equality Committee, advocating for inclusive policies and social equity. In the media sphere, Jamboria hosts the Redemption Broadcast Network (RBN) podcast, which addresses Sierra Leone's societal and developmental challenges, focusing on the social and psychological factors influencing human behaviour and national progress. He also manages a YouTube channels @RbnLiveTV that promotes advocacy for social justice, trust building and Youth Empowerment and the Aboulay Education vision, advocating for mother tongue languages in teaching to enhance education in Sierra Leone. Jamboria is the president of the ScanAfrik Foundation, an NGO that supports the interests of Africans in Norway and across the continent. He shares his insights through his blog on Google Blogger at redemptionnetwork.blogspot.com and on Salone Redeemer at https://saloneredeemer.com. His online radio platform can be accessed at rbnlive.webradiosite.com. Social Media Presence:

-

Twitter (X): @Boyejay

-

Instagram: @redemption_bn and @aboulayminds

-

WordPress: Salone Redeemer

Jamboria also contributes to The Patriotic Vanguard and other platforms, advocating for Sierra Leone’s development. For more insights, visit his blog, social media profiles, or listen to his online radio.

Sierra Leone is a nation that embodies a

paradox of cultural unity and political fragmentation. Despite being one of the

most culturally and religiously homogeneous countries in Africa, the country

remains deeply polarized along regional and partisan lines. The dominant

Islamic faith and the Fulani-Mande cultural foundation create profound

commonalities among Sierra Leone’s major ethnic groups, including the Mende,

Temne, Limba, and Mandingo. Inter-ethnic marriages, the widespread use of

common surnames, and the overlapping linguistic traditions suggest that the

country should, in theory, have a strong sense of national unity. However,

political fragmentation has persisted as a significant challenge, sustained by

historical legacies, elite manipulation, and institutional weaknesses. Unlike

many African nations where ethnic and religious divisions are the main sources

of conflict, Sierra Leone demonstrates how political identity can override

cultural commonalities, fuelling instability.

Political polarization in Sierra Leone has

been reinforced through decades of historical, colonial, and post-colonial

political manoeuvring. The two dominant parties, the All People’s Congress

(APC) and the Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP), have historically entrenched

regional loyalties and reinforced a winner-takes-all system of governance. This

political culture has created an environment where electoral victories often

lead to the systematic exclusion of the opposition, heightening political

tensions and fostering long-term instability. To understand why these divisions,

persist despite a shared cultural foundation, it is essential to examine Sierra

Leone’s historical trajectory, the role of secret societies, the importance of

inter-ethnic surnames, and the ways political elites have strategically

manipulated these identities to maintain power.

The political divisions in Sierra Leone have

deep roots in the colonial governance structures established by the British.

The colonial rulers implemented a dual system of governance, in which the north

was governed through indirect rule—granting significant administrative power to

local chiefs—while the south and east were subjected to direct rule under

colonial officers. This system created significant economic and infrastructural

disparities between the two regions, fuelling political competition and

long-term rivalries (Bangura, 2015).

At independence in 1961, these colonial

divisions continued to shape Sierra Leone’s political landscape. The SLPP,

which had led the independence movement, was largely associated with the Mende-dominated

south and east, while the APC, founded in the 1960s, built its political base

in the predominantly Temne and Limba northern regions. Over the decades,

political power has oscillated between these two dominant parties, each

reinforcing regional loyalties and prioritizing its strongholds over national

governance.

The civil war (1991–2002) further aggravated

these divisions. While the war was driven by grievances related to corruption,

economic marginalization, and centralized governance, it was also heavily

influenced by regional factionalism. The Revolutionary United Front (RUF)

insurgency, initially framed as a rebellion against state corruption, became

deeply entangled in regional power struggles. Though the war ended in 2002, the

mistrust it cultivated between political actors has continued to shape

electoral politics and governance, making it difficult for the country to move

beyond regional partisanship.

Despite the deep political divisions, Sierra

Leone remains remarkably homogeneous in cultural and linguistic identity. One

of the strongest indicators of this shared heritage is the prevalence of common

surnames across ethnic groups. Names such as Koroma, Kamara, Conteh, Bangura,

Fofanah, and Sesay are widely used among the Temne, Limba, Mandingo, and Mende

peoples. These surnames have deep historical origins, tracing back to Fulani,

Senegambian, Konyaka, Malinke, and Gbandi-Loko migrations that shaped Sierra

Leone’s demographics.

The Koroma surname is particularly

significant. While commonly associated with the Limba and Temne, it is also

found among the Mende-speaking population. This widespread presence reflects

the extensive influence of Mande heritage across Sierra Leone. Historically,

the Koroma name has been linked to warriors, traders, and political leaders who

played crucial roles in both pre-colonial and colonial Sierra Leone. Its

presence across ethnic groups also suggests historical ties to the Mali and

Songhai Empires, which facilitated the spread of Mande culture, language, and

surnames across West Africa.

Similarly, the Fofanah surname, widely

associated with the Mandingo, Temne, and Mende, has strong Senegambian roots.

Many Fofanah families trace their lineage to Fulani-Mande Islamic scholars and

traders who migrated southward from Mali and Guinea into Sierra Leone. Their

integration into different communities over centuries led to the widespread

adoption of the Fofanah name across various ethnic groups. Many individuals

bearing the Fofanah name have historically played key roles in Islamic

scholarship, governance, and commerce.

The Sesay surname is another example of a

Mande-Senegambian name that has been adopted across multiple ethnic groups in

Sierra Leone. Like the Fofanah name, Sesay is historically linked to Malian and

Senegambian expansions, particularly during the height of the Mali Empire’s

trade networks. Families with the Sesay name were influential in establishing trade

routes, religious schools, and political networks, facilitating economic and

social integration across different regions. The name’s widespread presence

across various districts reinforces the idea that Sierra Leone’s ethnic groups

have long been connected through trade, migration, and intermarriage.

Beyond surnames, place names in Sierra Leone

also reflect Mande, Fulani, and Senegambian influences. The Koya region, which

exists in both Port Loko and Kenema districts, directly references the Mane

warriors who established strongholds in Sierra Leone and the broader Mano River

Union region. The recurring names Gbendembu (in Bombali) and Nongowa (in

Kenema) highlight the influence of Gbandi, Loko, and Mande-speaking groups in

shaping Sierra Leone’s geographic and cultural landscape. The place name Sumbuya,

found in almost every district, further underscores the deep historical

interactions that have shaped Sierra Leone’s modern identity.

One of the most enduring cultural institutions

that binds Sierra Leone together is the predominance of Mande secret societies,

particularly the Poro and Sande societies. These secret societies, which

originated from the broader Mande cultural sphere, have played a critical role

in shaping political, spiritual, and social life in Sierra Leone.

The Poro society, which is primarily for men,

functions as an institution of governance, education, and moral regulation. It

serves as a training ground where political leaders and traditional elders are

taught leadership, conflict mediation, and societal laws. The Sande society,

the women’s counterpart, plays an equally vital role in the education and

initiation of young women, focusing on social responsibility, fertility, and

leadership.

Although originally associated with Mande-speaking

groups such as the Mende and Mandingo, these societies have been adopted by non-Mande

groups, including the Temne and Limba. The widespread presence of Poro and

Sande societies reinforces Sierra Leone’s cultural unity, even in the face of political

polarization. However, political elites have often exploited these secret

societies to consolidate power, maintain political loyalty, and suppress

opposition figures.

Despite its deep cultural homogeneity, Sierra

Leone remains politically divided due to historical legacies, elite

manipulation, and weak democratic institutions. However, the country’s shared

linguistic, religious, and historical heritage, including the widespread use of

inter-ethnic surnames and place names and the enduring influence of Mande

secret societies, provides a strong foundation for national unity. By prioritizing

institutional reforms, decentralization, and issue-based governance, Sierra

Leone can move beyond partisan conflicts and build a more cohesive national

identity.

References

- Bangura, Y. (2015). Democracy and identity conflict in Sierra

Leone: Reflections on the political landscape. African Affairs,

114(455), 224-246. - Conteh, M. (2019). Political favoritism and regional disparities

in Sierra Leone: A historical perspective. Journal of African Studies,

14(2), 89-102. - Fyle, C. (2006). Historical dictionary of Sierra Leone.

Scarecrow Press. - Little, K. (1965). The Political Function of the Poro Society in

Kpaa Mende society. Africa, 35(4), 349-365. - Sesay, A. (2020). Partisan governance and democratic

consolidation in Sierra Leone. West African Politics Journal, 12(3),

56-78.

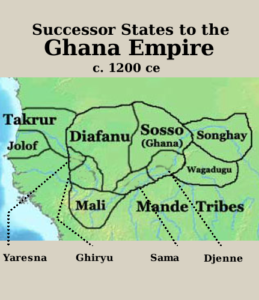

The history of the medieval Western Sudan is a

tapestry of empires that shaped the region’s political, cultural, and economic

trajectories. While much has been written about the Ghana, Mali, and Songhay

empires, the Susu kingdom remains a lesser known but equally important chapter

in this narrative. This article explores the Susu kingdom’s historical

relevance, geographical reach, and enduring connections to the Mano River and

Sierra Leone, drawing on oral traditions, medieval chronicles, and Portuguese

records. Stephan Bühnen’s (1994) insightful work provides the foundation for

this exploration.

The Rise

and Influence of the Susu Kingdom

The Susu kingdom rose to prominence after the

decline of Ghana and before the rise of Mali, dominating the Futa Jalon and

Sankaran regions. This kingdom leveraged its strategic location and economic

resources, particularly its access to gold from the Bure mines, to become a

significant regional power (Bühnen, 1994). Its influence extended to the Upper

Niger and beyond, reaching regions close to the Mano River basin. Unlike Ghana

and Mali, Susu’s prominence south of Arab trade routes has contributed to its relatively

limited documentation in medieval Arabic sources.

The Susu people established political and

economic structures that laid the foundation for their later connections to

Sierra Leone and the Mano River region. The kingdom’s decline began with the

rise of Mali under Sunjata Keita and culminated in the 18th century with the

Fula jihad, but the Susu people’s legacy endured in their migration and

cultural influence across the region.

The Susu

and the Mano River Region

The Susu’s geographical and historical ties to

the Mano River region are deeply rooted in their migrations, trade networks,

and cultural exchanges. Following the decline of their kingdom, the Susu moved

southward, settling in areas near the modern-day borders of Guinea, Liberia,

and Sierra Leone. These migrations brought them into contact with ethnic groups

such as the Mende, Temne, and Kissi, influencing the demographics and cultural

practices of the region.

The Mano River served as a vital waterway for

trade, linking inland goldfields with coastal trade centers. The Susu, known

for their expertise in trade and mining, played a pivotal role in facilitating

the exchange of goods such as gold, kola nuts, and salt. Portuguese records

from the 15th and 16th centuries document the Susu’s active participation in

these networks, particularly along the coasts of Guinea and Sierra Leone

(Bühnen, 1994).

Cultural

and Religious Influence in Sierra Leone

The Susu’s migration into Sierra Leone had a

lasting impact on the region’s cultural and religious landscape. Their early

adoption of Islam contributed to the spread of Islamic practices in the Mano

River basin and Sierra Leone. The Susu’s integration into local communities

also influenced linguistic and cultural exchanges. For example, the Susu

language, part of the Mande family, shares similarities with languages spoken

in Sierra Leone, reflecting their historical interactions and intermarriages.

In addition to their linguistic and religious

contributions, the Susu introduced governance practices that shaped local

chieftaincies. Oral traditions in Sierra Leone often highlight the Susu’s role

in establishing political structures, emphasizing their historical significance

in the region.

Portuguese

Accounts and European Records

European explorers and traders, particularly

the Portuguese, encountered the Susu during their coastal expeditions. These

records provide valuable insights into the Susu’s role as intermediaries in

regional trade. The Portuguese described the Susu as key players in gold

exports, which linked the inland economies of the Western Sudan to the

burgeoning global trade networks of the Atlantic (Bühnen, 1994). These accounts

also highlight the Susu’s presence in Sierra Leone and their connections to the

Mano River basin.

Sankaran

and the Susu Legacy

The Sankaran region, identified as the

heartland of the Susu kingdom, remained a significant power centre even after

the kingdom’s decline. The Konte lineage, central to Sankaran’s governance,

continued to exert influence, preserving the memory of Susu’s imperial past.

Bühnen (1994) notes that Sankaran’s traditions, including those preserved in

the Sunjata epic, reflect the cultural and political importance of the region.

The Susu’s transition into polities like Jalo

and their eventual absorption into the Muslim Fula state of Futa Jalon

illustrate a pattern of continuity and adaptation. Despite losing political

independence, the Susu maintained their identity, leaving a lasting imprint on

the cultural and political fabric of the Mano River region and Sierra Leone.

Conclusion

The Susu kingdom represents a critical yet

understudied chapter in West African history. Its influence extended from the

Futa Jalon and Sankaran regions to the Mano River and Sierra Leone, shaping

trade, culture, and religion. By examining oral traditions, chronicles, and

European records, scholars like Stephan Bühnen (1994) have illuminated the

Susu’s enduring legacy. Today, their contributions remain a testament to the

dynamic interplay of migration, trade, and cultural exchange in precolonial

Africa.

References

Bühnen, S. (1994). In quest of Susu. History

in Africa, 21, 1–47.https://www.jstor.org/stable/3171880

Introduction

From the early trade networks that linked the Upper Guinea Coast to the trans-Saharan and Atlantic economies, to the influence of Islam, Christianity, and colonialism, this article explores the region’s dynamic history. Through six key themes, it examines the sociocultural adaptations that have defined the Upper Guinea Coast, emphasizing resilience and cultural innovation.

In the 10th century, the Upper Guinea Coast was home to diverse societies that relied on agriculture, fishing, and local trade. Indigenous communities developed sophisticated irrigation systems, particularly for African rice cultivation, a crop domesticated in the region (Carney, 2001). Coastal communities thrived on fishing, which not only sustained their diets but also served as a key trade commodity.Ethnic and linguistic diversity characterized the region, with languages from the Mande, Mel, and Atlantic families reflecting centuries of migration and interaction (Green, 2019). Clan-based social systems, bolstered by oral traditions, provided a framework for governance and social cohesion. Rituals and spiritual practices, often tied to the natural environment, underscored the interconnectedness of human and ecological systems.

The trans-Saharan trade, linking West Africa to North Africa and the Mediterranean, integrated the Upper Guinea Coast into a larger economic network. Gold, ivory, and kola nuts from the region were exchanged for salt, textiles, and horses, with Islamic traders introducing new governance ideas and religious practices (Curtin, 1971). The rise of coastal trade hubs facilitated urbanization and cultural exchange. Ports such as Bissau became melting pots, fostering interaction between diverse ethnic groups and stimulating local industries like weaving and metalworking (Brooks, 1993). Islamic influence further transformed the region, blending with local traditions and contributing to education and governance.

European contact, beginning with the Portuguese in the 15th century, marked a turning point for the Upper Guinea Coast. Initially centered on mutually beneficial trade, European interests shifted toward the transatlantic slave trade, profoundly destabilizing local societies (Rodney, 1970). Coastal elites, drawn into the trade, restructured their economies and political systems to meet European demand. Colonial powers imposed centralized governance structures, undermining traditional systems and fostering economic dependency. The suppression of indigenous cultures and forced labor systems exacerbated social inequalities. Yet, resistance to colonization and cultural resilience remained evident, laying the groundwork for independence movements in the 20th century (Amin, 1972).

Globalization introduced new pressures, including migration and climate change. Communities adapted by drawing on traditional knowledge to address issues such as environmental degradation and social fragmentation. Anthropological studies highlight how cultural preservation and innovation coexist, enabling societies to navigate these modern challenges (Fairhead & Leach, 1996).

Syncretic religious practices, blending indigenous, Islamic, and Christian traditions, reflect the region’s adaptability. Today, religious institutions play critical roles in community development and conflict resolution, highlighting the enduring relevance of spiritual life in the region (Gray, 1980).

Cultural preservation efforts, from documenting endangered languages to promoting traditional crafts, are vital in addressing the challenges of globalization. These initiatives emphasize the region’s role as a case study in human resilience and cultural innovation (Jackson, 1985).

Class and respect dynamics within African societies and the African diaspora represent an intricate interplay of history, culture, and socio-economic structures. These issues are deeply rooted in pre-colonial traditions, colonial disruptions, and modern global influences. Understanding how class stratification and respect norms have evolved within African communities requires examining their historical context, cultural manifestations, and potential pathways forward.

Historical Roots of Class and Respect in African Societies

Historically, African societies have always exhibited forms of stratification, though these were largely fluid and communal. In many pre-colonial African cultures, respect was tied to age, wisdom, and communal contributions rather than material wealth or rigid class divisions. For example, elders were revered as custodians of knowledge and decision-makers within many African tribes, a value system that still persists in parts of the continent today (Mbiti, 1990).

Colonialism profoundly disrupted these traditional systems. European powers imposed exploitative economic systems and hierarchical social orders that undermined indigenous values. The introduction of cash economies and land ownership laws created stark divides between the elite, often educated and European-aligned Africans, and the rest of the population. These colonial class systems, supported by divisive governance tactics, solidified a culture of economic disparity and social stratification (Rodney, 1972).

Manifestations of Class and Respect Issues Today

In contemporary African societies, class and respect issues are deeply intertwined. Economic inequality, a legacy of both colonial exploitation and neo-colonial structures, exacerbates class tensions. Wealth, often concentrated in urban centers or among those connected to political elites, has become a significant determinant of respect in many communities. This shift represents a departure from traditional respect systems based on character, age, or community contributions.

Intra-community Dynamics

Within families and local communities, respect is frequently tied to material success. For example, younger family members who achieve financial stability may be expected to command respect from elders, challenging traditional age-based hierarchies. This tension is particularly evident in the African diaspora, where western individualism sometimes clashes with African collectivist values.

Gender and Intersectionality

Gender plays a critical role in respect and class dynamics. Patriarchal traditions often confer respect based on male authority, while women’s contributions—whether economic or domestic—may be undervalued. However, modern movements advocating for gender equality are challenging these norms. For instance, women-led businesses and organizations are reshaping respect dynamics by emphasizing merit over tradition.

Diaspora Perspectives

The African diaspora adds another layer of complexity. Africans living outside the continent often face external class and racial hierarchies, which intersect with internal respect norms. For instance, African immigrants in Western countries may experience a loss of social status due to systemic racism, even as they navigate respect expectations within their own communities.

The Cultural Significance of Respect

Respect is a cornerstone of African cultures, deeply embedded in language, customs, and social interactions. In many African societies, greetings reflect hierarchical respect. For instance, in Yoruba culture, younger individuals prostrate or kneel to greet elders, symbolizing deference and honor (Fasoranti, 2018). Similarly, Zulu culture emphasizes the importance of ubuntu—a philosophy of mutual respect and interconnectedness.

However, globalization and modernity are challenging these norms. The rise of individualism, consumerism, and digital cultures has diluted traditional respect systems. Social media, for example, often amplifies materialism, with wealthier individuals gaining admiration regardless of their ethical or communal contributions.

Bridging Class Divides and Fostering Respect

Addressing class and respect issues requires a multifaceted approach:

1. Education and Awareness: Promoting education about the historical roots of class and respect systems can help communities critically examine and reshape these dynamics. For example, integrating African philosophy and history into school curricula can foster a deeper appreciation for traditional values.

2. Economic Empowerment: Tackling economic disparities is essential for reducing class-based tensions. Programs that support entrepreneurship, especially among marginalized groups, can create pathways to equitable respect.

3. Cultural Revitalization: Encouraging a return to respect systems based on character and community contributions can counteract materialistic values. Cultural festivals, storytelling, and intergenerational dialogues are effective tools for this purpose.

4. Diaspora Engagement: Bridging gaps between African communities on the continent and in the diaspora can foster solidarity. Initiatives such as exchange programs, pan-African cultural events, and advocacy for racial justice can unite Africans globally.

Conclusion

The interplay of class and respect issues among African communities reflects a complex legacy of history, culture, and contemporary realities. While colonialism and globalization have reshaped traditional norms, there is an opportunity to reclaim and adapt these values to foster unity and equity. By addressing economic disparities, promoting cultural pride, and encouraging intergenerational dialogue, African societies can navigate these challenges and build a future where respect transcends class divides.

References

1. Fasoranti, M. (2018). Yoruba Culture and Traditions: A Handbook. Ibadan University Press.

2. Mbiti, J. (1990). African Religions and Philosophy. Heinemann.

3. Rodney, W. (1972). How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications.

4. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2013). Coloniality of Power in Postcolonial Africa: Myths of Decolonization. CODESRIA.

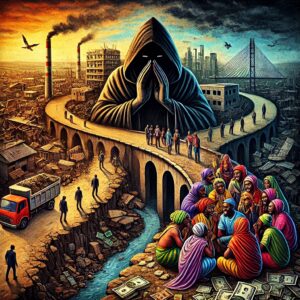

Falsehoods, deceptions, lies, and the social parameters informing corruption significantly undermine stability and development in Sierra Leone. These factors erode public trust, weaken institutions, and impede socioeconomic progress. The following analysis explores these impacts, supported by scholarly references in APA style.

Erosion of Trust and Institutional Integrity

The prevalence of corruption in Sierra Leone has deep historical roots, contributing to the nation’s fragility and instability. Abdulai and Kubbe (2023) examine the diverse facets of corruption, noting that it permeates various aspects of society and governance, thereby hindering sustainable development efforts.

Socio-Cultural Norms and Corruption

Societal perceptions and traditional practices can either deter or enhance acts of corruption. Jamboria (2023) discusses how social thinking and perceptions in Sierra Leone influence corrupt behaviors, emphasizing the need for a consensus within society to curb corruption for continued stability and development.

Impact on Socio-Economic Development

Corruption adversely affects income distribution, investment, government budgets, and economic reforms. Saidu (2023) highlights that corruption increases inequality, decreases accountability, and produces rising frustration among citizens, thereby hindering socio-economic development in Sierra Leone.

Undermining Governance and Service Delivery

Corruption within local government structures leads to poor service delivery and erodes public confidence in governance. Koroma et al. (2023) highlight that corruption significantly undermines the efficiency of local administrations, leading to poor service delivery and eroding public confidence in governance structures.

Conclusion

Falsehoods, deceptions, lies, and the social parameters informing corruption have multifaceted adverse effects on Sierra Leone’s stability and development. They erode trust in institutions, exacerbate corruption, impede development efforts, undermine social cohesion, and weaken the rule of law. Addressing these challenges requires a concerted effort to promote transparency, strengthen institutional frameworks, and enhance media literacy among the populace.

References

- Abdulai, E. S., & Kubbe, I. (2023). The Diverse Facets of Corruption in Sierra Leone. Springer.

- Jamboria, M. B. J. (2023). Social Parameters of Corruption and Status in Sierra Leone: How Our Social Thinking and Perceptions Enhance or Deter Acts of Corruption. In E. S. Abdulai & I. Kubbe (Eds.), The Diverse Facets of Corruption in Sierra Leone (pp. 73-89). Springer.

- Saidu, F. (2023). The Impact of Corruption on the Socio-Economic Development of Sierra Leone: A Case Study of Bo City. International Journal of Scientific Development and Research.

- Koroma, S. M., Yusuf, M., Dauda, E., & Gando, J. G. T. (2023). The Effects of Corruption on Local Government Service Delivery in Sierra Leone: The Case of Bonthe District Council. International Journal of Scientific Development and Research.