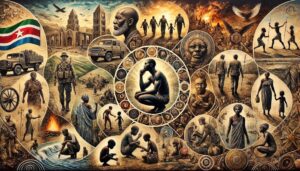

Sierra Leone, a nation rich in culture and natural resources, has endured centuries of trauma that shape its social fabric and behavioural patterns. From the precolonial period through colonialism, civil war, and the more recent Ebola epidemic, the people of Sierra Leone have faced profound challenges that have left psychological and societal scars. This article explores the historical and recent traumas endured by Sierra Leoneans and examines how these experiences manifest in behaviours deeply rooted in survival instincts. The analysis highlights the barriers these behaviours create to societal cohesion and development, underscoring the urgent need for holistic healing and nation-building.

Historical Context of Trauma in Sierra Leone

Colonial rule further deepened societal fissures. The British colonizers imposed artificial boundaries, fostered ethnic divisions, and exploited the country’s resources, prioritizing their economic interests over the well-being of the indigenous population (Kup, 1975). The colonial administration’s “divide and rule” tactics exacerbated mistrust among ethnic groups, creating a hierarchy that privileged certain communities over others. These historical grievances remained unresolved, creating a fertile ground for future conflicts.

Post-Colonial Struggles and the Civil War

The civil war left deep psychological scars. Survivors often suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), while communities became fragmented by mistrust and fear. Many individuals adopted survival-oriented behaviours, focusing on self-preservation in an environment where betrayal and violence were pervasive. These behavioural patterns, rooted in wartime experiences, continued to influence interpersonal and community relationships long after the conflict ended (Betancourt et al., 2010).

Recent Trauma: The Ebola Epidemic

The Ebola crisis also highlighted systemic failures in governance and resource allocation. Many Sierra Leoneans lost faith in public institutions, perceiving them as ineffective or corrupt. This erosion of trust, coupled with the trauma of losing loved ones, reinforced survival-oriented behaviours characterized by fear, self-protection, and a focus on immediate needs.

Behavioural Manifestations of Trauma

Timidity and Reluctance to Take Risks

The historical and recent traumas experienced by Sierra Leoneans have cultivated a widespread timidity and reluctance to take risks. Survival instincts, honed over generations, often discourage individuals from engaging in activities perceived as uncertain or threatening. For example, entrepreneurial ventures and collective action require a level of risk tolerance and trust in others that many Sierra Leoneans find difficult to muster. This hesitancy stifles innovation and economic progress, perpetuating cycles of poverty and stagnation.

Distrust and Fragmentation

Distrust is a pervasive legacy of Sierra Leone’s traumatic history. Whether stemming from colonial divisions, wartime betrayals, or the inadequacies of public institutions during the Ebola crisis, this lack of trust undermines collective action and community cohesion. Individuals often prioritize their immediate, personal needs over shared goals, leading to fragmented communities where collaboration is rare.

This distrust also manifests in governance. Citizens are sceptical of political leaders, perceiving them as self-serving rather than serving the public interest. Such scepticism discourages civic engagement, weakening democratic institutions and perpetuating a cycle of ineffective governance and societal disillusionment (Fanthorpe, 2001).

Blaming and Complaining as Coping Mechanisms

Barriers to Development and Societal Cohesion

The cycle of mistrust and survival-oriented behaviour also perpetuates socioeconomic inequalities. Those with access to resources prioritize their immediate needs, often at the expense of long-term development. This focus on short-term gains undermines efforts to build sustainable systems and institutions, leaving the nation vulnerable to future crises.

Breaking the Cycle: Toward Healing and Development

Addressing the legacy of trauma in Sierra Leone requires a multifaceted approach that prioritizes healing, trust-building, and collective action. Several strategies can contribute to breaking the cycle:

Psychosocial Support: Providing access to mental health services can help individuals and communities process trauma and develop resilience. Community-based healing initiatives, including storytelling and traditional practices, can foster reconciliation and trust.

Strengthening Institutions: Rebuilding trust in public institutions requires transparency, accountability, and equitable resource distribution. Strengthening governance and delivering tangible benefits to citizens can restore faith in leadership and encourage civic engagement.

Promoting Collective Action: Encouraging grassroots movements and community-driven development initiatives can foster collaboration and a sense of shared purpose. Programs that emphasize local ownership and participation can empower communities to address common challenges.

Education and Capacity Building: Investing in education and skill development can equip individuals with the tools to overcome fear and take calculated risks. Entrepreneurial training and support for small businesses can promote economic growth and reduce dependency on survival-oriented behaviours.

Reconciliation Efforts: Addressing historical grievances through truth-telling and reconciliation initiatives can help heal divisions and build a foundation for trust and unity. Inclusive policies that celebrate Sierra Leone’s diverse cultural heritage can also promote national cohesion.

References